Bundlers and RSCs: A Tale of Two Runtimes

1. Motivation and Background

The precursor to this article is that RSCs as a feature of React are heavily dependent on Bundlers like Vite, Parcel, Webpack/Turbopack. I initially presented this as a talk along with my friend at a React Meetup in Bengaluru, India. I was inspired by Dan Abramov’s Blog on the same topic.

I don’t want to explore a production-ready solution here, I leave that to the experts.

Why do React Server Components, a core React feature, depend so heavily on bundlers? It comes off as counter-intuitive to me. Historically, bundlers have mostly optimized client-side builds (code that actually runs in the browser). Server Components, on the other hand, run on the server. So why does a server-side feature care about client tooling at all? Further, if RSCs have to be dependent on Bundlers, then why doesn’t the core team ship a native React solution for it? Why depend on Bundlers to do the job? This article is basically my lab notebook for trying to resolve that seemingly strange dependency.

Don’t worry if that last paragraph doesn’t make much sense. By the end of this article, you should feel right at home with it. I’ll use technical jargon sparingly and I have avoided any usage of external libraries too. So yes, everything is right here and bare. All of the code in this article is made available on GitHub.

However, to truly appreciate the article it is best if you have some background on following:

- JavaScript

- HTTP Server in Node.js

All the other relevant background (including a bit about Bundlers) is covered in this article. That said, I’ve taken loads of liberty in leaving out the details of real-world implementations in favor of making it accessible to (almost) everyone!

So let’s dive into it.

2. Unpacking Bundlers

Bundlers aim to solve many problems. I don’t plan to go into all of them however I found this Reddit Post which does a good job in listing all of them. For the purpose of this article, only one of them is relevant to us: Dependency Resolution.

Bundlers generate and store dependency graphs which can later be used as an index for fast retrieval of components. I demonstrate this through some code.

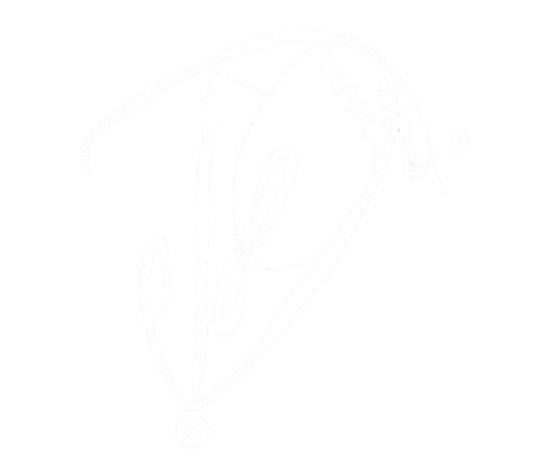

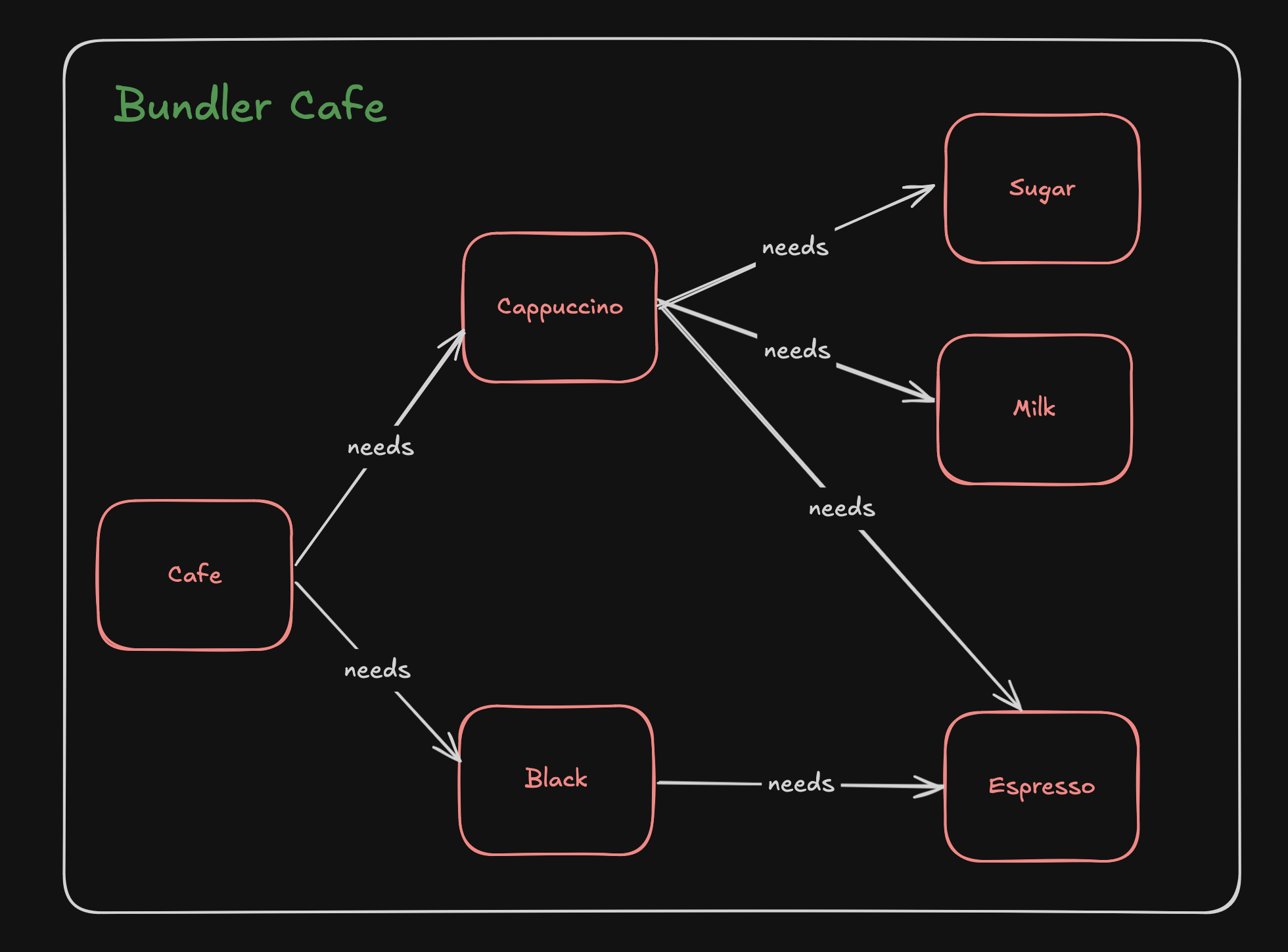

Let me introduce you to Bundler Cafe! This cafe serves 2 drinks, Cappuccino and Black Coffee. The raw materials needed for this are Espresso, Milk and Sugar. A rough way to model this is:

Following is a simple JavaScript implementation of the same:

Cafe.js

import { Black } from './Black.js';

import { Cappuccino } from './Cappuccino.js';

function Cafe() {

console.log('Menu');

Black();

Cappuccino();

}

Cafe();Cappuccino.js

import { Espresso } from './Espresso.js';

import { Milk } from './Milk.js';

import { Sugar } from './Sugar.js';

export function Cappuccino() {

console.log('Cappuccino contents:');

Espresso();

Milk();

Sugar();

}Black.js

import { Espresso } from './Espresso.js';

export function Black() {

console.log('Black contents:');

Espresso();

}Espresso.js

export function Espresso() {

console.log("\tEspresso shot");

}Milk.js

export function Milk() {

console.log('\tMilk: steam + foamed');

}Sugar.js

export function Sugar() {

console.log('\tSugar: Sweetens the Coffee');

}When I run node Cafe.js in my terminal, the output looks something like this:

Now, the bundler performs three actions here:

- Identify Entry points (all our source files:

Cafe.js,Cappuccino.js,Black.js,Espresso.js,Milk.js,Sugar.js) - Process Dependency Graphs: For each file, identify the complete list of dependencies (including nested)

- Generate

manifest.json: Add the dependency graph in a file to perform look ups later

Here is how manifest.json would look like in our case:

{

"Espresso": ["Espresso.js"],

"Milk": ["Milk.js"],

"Sugar": ["Sugar.js"],

"Black": ["Espresso.js","Black.js"],

"Cappuccino": ["Espresso.js","Milk.js","Sugar.js","Cappuccino.js"],

"Cafe": ["Espresso.js","Black.js","Milk.js","Sugar.js","Cappuccino.js","Cafe.js"]

}This looks trivial and boring, but it’s exactly the kind of index which can be used to load dependencies, especially without having to read through the code present in any of the files. I’ve written a minimalistic Bundler implementation for this. However, there is no need to understand the implementation here.

This operation is usually done during the build phase of the application, before the client build is sent to the browser. The core idea here is that the Bundler preprocesses the source code and resolves the dependencies beforehand. This is useful because the server/build already did the work of figuring out what depends on what. So at runtime the browser can be told ‘go fetch these 5 things right now’ instead of discovering them one by one. This reduces the website response time significantly as all dependencies are loaded simultaneously!

3. Simplified Server Component Implementation

Time to introduce the browser and the server then. In this example, we have a simple index.html file which have the script index.js loaded in it. Here is how they look like.

index.html

<html>

<head>

<title>RSC and Bundlers: Tale of two runtimes</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="index.css">

</head>

<body>

<div id="app"></div>

<script type="module" src="/index.js"></script>

</body>

</html>index.js

import { deserialize } from "./utils/serialize.js";

import { Cafe } from "./src/Cafe.js";

const REGISTRY = { Cafe };

async function main() {

const res = await fetch("/page");

const data = await res.json();

const root = document.getElementById("app");

root.innerHTML = data.html;

data.components.forEach((c, i) => {

deserialize({ entry: c, i }, root, REGISTRY);

});

}

main();index.js simply makes an API call to the server at the endpoint /page . The result is deserialised and set as the html of the root so that the result can be displayed. Adding some bit of styles in index.css and following is how your webpage looks like:

Serialisation is how the HTML component is sent over the wire to the browser and the browser deserialises it before rendering it on the browser. Another note here is that this is not React’s actual RSC protocol. I have deliberately boiled it down to show the moving parts. The point here isn’t to faithfully reconstruct server components, this YouTube video does a good job on it already.

Now, let’s now have a look at the server, contained in the file app.js .

app.js

import http from "node:http";

import { serialize } from "./utils/serialize.js";

function ServerComponent({ name }) {

return `<p style="font-style:italic">Hello ${name} from the Server Component</p>`;

}

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

if (req.url.startsWith("/page")) {

const html = `

<div>

<h1>RSC simplified demo</h1>

${ServerComponent({ name: "Bangalore" })}

<Cafe />

</div>

`;

const payload = serialize(html); // { html, components: [...] }

res.writeHead(200, {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

});

res.end(JSON.stringify(payload));

}

});

server.listen(3002, () => {

console.log(`Server running at http://localhost:3002/`);

});Notice how <Cafe /> is neither imported nor even defined in the file. That is because Cafe is a client-side component. It would be available in the build along with our other items on the menu (Cappuccino, Black, Espresso…). The server doesn’t send the component over the wire. It is on the browser to load the component first to be able to render the server component.

So far so good then. However, to spice stuff up just a little bit, let’s add some element of reactivity here rather than everything just being static components.

Let us add a db.json into the equation for our inventory management.

db.json

{

"isMilkAvailable": true,

"isEspressoAvailable": true

}With both available, our cafe can serve both Black coffee as well as Cappuccino. With only Espresso available, only Black coffee can be served and with only Milk available, our cafe cannot serve any coffee and the menu is empty. We tweak some logic in Cafe.js and start passing these new values from our unnamed server component to the browser as follows:

Updated server function in app.js

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

if (req.url.startsWith("/page")) {

const db = JSON.parse(readFileSync(join(ROOT, "db.json"), "utf8"));

const showCappuccino = db.isMilkAvailable;

const showBlack = db.isEspressoAvailable;

const html = `

<div>

<h1>RSC simplified demo</h1>

${ServerComponent({ name: "Bangalore" })}

<Cafe showCappuccino="${showCappuccino}" showBlack="${showBlack}" />

</div>

`;

const payload = serialize(html); // { html, components: [...] }

res.writeHead(200, {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

});

res.end(JSON.stringify(payload));

}

});and voilà! Here is how the results look like:

Congratulations! You now have a basic understanding about what a Server Component is! I encourage you to tinker more with the concept. It is fascinating!

Now, let’s try throttling our network and observe. At a 3G network following happens:

Notice how each one of the component loads one by one. More importantly notice how the dependency of a component only starts loading once the parent is started to load. So the browser is piecing together all the required files after the request to load the page is sent. Without extra help, the browser only learns about deeper dependencies after it’s already started loading their parents.

Only if there were a way to know all the dependencies in one shot itself…

4. Bundler-integrated implementation

The plan is simple here. During build phase itself, the bundler generates a dependency graph and stores it as manifest.json on the server-side. Now at runtime, the server not only sends the server component but it also shares all the client-side dependencies of the requested component (with the help of manifest.json which can generated at build time). The dependencies are shared as references, i.e. as file paths in the build folder (the folder which client already has i.e. src/Cafe.js).

So let’s modify our code according then. First up, we update our server-side function to also send the information present in manifest.json.

app.js: compute preloads server function

import { readFileSync } from "node:fs";

import { join } from "node:path";

const ROOT = process.cwd();

const manifest = JSON.parse(readFileSync(join(ROOT, "manifest.json"), "utf8"));

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

if (req.url.startsWith("/page")) {

const db = JSON.parse(readFileSync(join(ROOT, "db.json"), "utf8"));

const showCappuccino = db.isMilkAvailable;

const showBlack = db.isEspressoAvailable;

const html = `

<div>

<h1>RSC simplified demo</h1>

${ServerComponent({ name: "Bangalore" })}

<Cafe showCappuccino="${showCappuccino}" showBlack="${showBlack}" />

</div>

`;

const payload = serialize(html); // { html, components: [...] }

// Attach manifest for client to know the mappings

payload.preload = computePreload(payload.components);

res.writeHead(200, {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

});

res.end(JSON.stringify(payload));

}

});

function computePreload(components) {

const urls = new Set();

for (const c of components) {

(manifest[c.name] || []).forEach((u) => urls.add(u));

}

return [...urls];

}Notice how server, along with the html and the component, is also sending an additional attribute of preload here. Now we need to teach our client-side index.js to inject the preloads along with the server component all at once (and not after parsing through each of the client-side components).

index.js: Inject preloads

import { deserialize } from "./utils/serialize.js";

import { Cafe } from "./src/Cafe.js";

const REGISTRY = { Cafe };

async function main() {

const res = await fetch("/page");

const data = await res.json(); // { html, components }

// Preload *before* we mount

injectPreloads(data.preload);

const root = document.getElementById("app");

root.innerHTML = data.html;

data.components.forEach((c, i) => {

deserialize({ entry: c, i }, root, REGISTRY);

});

}

export function injectPreloads(urls = []) {

urls.forEach((u) => {

const link = document.createElement("link");

link.rel = "modulepreload";

link.href = `/src/${u}`;

document.head.appendChild(link);

});

}

main();Putting both these individual pieces together, here’s how the result looks like now (on a throttled network):

Notice the difference?

Now you would say, my network is never this slow. To that I say, does your codebase only have 5 javascript files with nothing but console logs?

As the codebase grows, the effects of such an optimisation are evident (to the point that it is impractical to not use bundler’s help here). That said, here lies a bundler-less implementation of RSCs, feel free to tinker with it as you like!

So this is how a Bundler integrates with RSCs. Addressing our earlier question, “If server components are meant to run on the server, why do they rely so heavily on client-side tooling?” Now we know the answer. It is to smoothly integrate with the client-side components. Bundlers bridge the gap that lies between a server component and it’s children client components.

The meta-theme here is also worth noting. The reason React depends on bundlers for this is because Bundlers have been doing this efficiently for decades now. When we develop new features, oftentimes we forget how to evaluate how they integrate with the existing ecosystem. By being clever enough, we can make our existing toolchains function in more than one way. It’s worth pausing and asking that question the next time you take on a new feature.

5. Credits and References

This article wouldn’t have been possible without:

- Dan Abramov, who wrote about this topic in his blog (check out his amazing blog here)

- React Meet up Bengaluru, who gave me the platform to speak about it.

- Raghav Khanna, my friend who came up with the idea to give the talk in the first place.

Here are some other useful websites on this topic:

- React Server Components from Scratch video by Ben Holmes

- React Serialise package which we borrowed our react-serialise functions from

- JavaScript Bundler from Scratch video by Nakazawa Tech

- A Reddit post for Comprehensive list of problems a Bundler solves

Bonus: Enough with toy code. Let’s look at how the big boys at Parcel have implemented it. Fair warning: as it’s production grade code, it isn’t the most simplified code and I don’t plan to do a comprehensive explanation either. Feel free to skip the next section entirely.

Thanks for reading!

Bonus: 6. Parcel Implementation

As of writing this blog, Parcel support for RSCs is still in beta. You can find more details about the support here.

We however, are more interested in how the manifest.json is generated during the build, used by the server to communicate additional dependencies and how the client utilises this information to preload the modules.

To begin with, this file in the Official Parcel repository is responsible for generation of Dependencies. Here is how the Dependency type is defined in the code:

type DependencyOpts = {|

id?: string,

sourcePath?: FilePath,

sourceAssetId?: string,

specifier: DependencySpecifier,

specifierType: $Keys<typeof SpecifierType>,

priority?: $Keys<typeof Priority>,

needsStableName?: boolean,

bundleBehavior?: ?IBundleBehavior,

isEntry?: boolean,

isOptional?: boolean,

loc?: ?SourceLocation,

env: Environment,

packageConditions?: Array<string>,

meta?: Meta,

resolveFrom?: ?FilePath,

range?: ?SemverRange,

target?: Target,

symbols?: ?Map<

Symbol,

{|local: Symbol, loc: ?SourceLocation, isWeak: boolean, meta?: ?Meta|},

>,

pipeline?: ?string,

|};As you can notice, unlike our dependency (which merely consisted of sourcePath), there are various other attributes which are kept tracked of, like id, priority, isOptional, etc. However, none of this is unique to RSCs. The Bundler is going to do this regardless.

Where the bundler integration comes to life is this particular folder in the repository. These functions provide the necessary bindings which are further used in React’s repository, i.e. these are the APIs that RSC frameworks like Next.js use under the hood.

Here is the React-side code. Remember our tiny manifest.json that mapped component names to file paths? React’s serverManifest is the grown-up version of that.

server-side manifest

let serverManifest: ServerManifest = {};

export function registerServerActions(manifest: ServerManifest) {

// This function is called by the bundler to register the manifest.

serverManifest = manifest;

}Further, this file utilises the manifest to resolve dependencies. Here is the snippet for client components resolution on the server.

export function resolveClientReferenceMetadata<T>(

config: ClientManifest,

clientReference: ClientReference<T>,

): ClientReferenceMetadata {

if (clientReference.$$importMap) {

return [

clientReference.$$id,

clientReference.$$name,

clientReference.$$bundles,

clientReference.$$importMap,

];

}

return [

clientReference.$$id,

clientReference.$$name,

clientReference.$$bundles,

];

}Finally, this file, on the client resolves server reference and preloads the references. Following is the snippet present in the file:

export function resolveClientReference<T>(

bundlerConfig: null,

metadata: ClientReferenceMetadata,

): ClientReference<T> {

// Reference is already resolved during the build.

return metadata;

}

export function resolveServerReference<T>(

bundlerConfig: ServerManifest,

ref: ServerReferenceId,

): ClientReference<T> {

const idx = ref.lastIndexOf('#');

const id = ref.slice(0, idx);

const name = ref.slice(idx + 1);

const bundles = bundlerConfig[id];

if (!bundles) {

throw new Error('Invalid server action: ' + ref);

}

return [id, name, bundles];

}

export function preloadModule<T>(

metadata: ClientReference<T>,

): null | Thenable<any> {

if (metadata[IMPORT_MAP]) {

parcelRequire.extendImportMap(metadata[IMPORT_MAP]);

}

if (metadata[BUNDLES].length === 0) {

return null;

}

return Promise.all(metadata[BUNDLES].map(url => parcelRequire.load(url)));

}This is how Parcel bindings for RSCs are implemented currently.